In the last half of the 19th century, the city of Saint Paul gained a reputation as a wonderful summer destination but a horrible place to be in the winter. In 1885 a New York reporter, upon his return home after visiting the area, wrote that Minnesota was “another Siberia, unfit for human hibernation in the winter.” On October 31, 1885, a group of “about fifty or sixty” leading St. Paul businessmen met at the Ryan Hotel and discussed ways to promote the winter splendor of the area. They hoped to show that St. Paul was an amazing place year-round.

The group settled on holding a winter carnival and building an Ice Palace. They hoped to replicate the success that the city of Montreal had found after their first winter carnival in 1883. These businessmen felt that a carnival would show the year-round value of the city. It also would be “worth a great deal of money.” Not only would it promote the area, but it was a chance to advertise the wherewithal of the citizens of Saint Paul. They felt that a carnival would turn the winter season into one of “continuous enjoyment.”

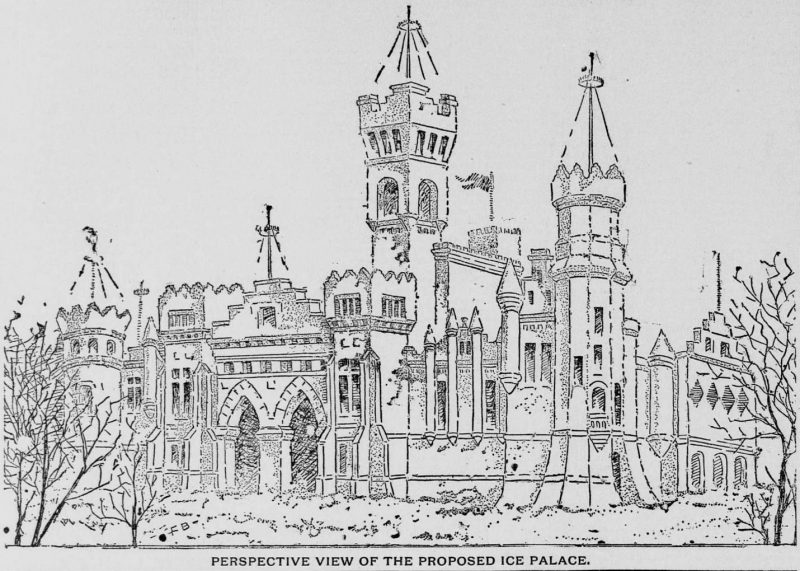

Business leaders felt they needed a “hook”, a grand reason for people to come to the area to take part in their winter celebration. They decided that they would have a massive ice castle built. It would be the attraction at the center of everything, with an interior housing “booths of all kinds and stands for bands and orchestras.

The measure was approved by the group. It was decided that $12,000 dollars would be enough to raise the grand structure. The building cost was significant but everyone in attendance felt it was realistic for what they hoped to accomplish. Easy accessibility to lots of ice, and a climate that would preserve the palace for a prolonged amount of time were seen as additional unique benefits. The St. Paul Winter Carnival and Ice Palace Association would raise the money through the sale of stocks at $25 per share. Central Park would eventually be named the location of the ornate palace of ice and be a boon for the city in the coming winter. The palace would give people from everywhere “something to gaze on.”

The ice structure would be modeled after the grand palaces of Europe. The goal was to replicate their “pleasing and substantial architecture.” The finished structure would stand one hundred and forty long and one hundred feet high. The palace would have thirty foot high walls and boast a tower reaching one hundred twenty feet into the sky. It would be “illuminated with electricity” and have emblematic and fantastic shapes frozen into the ice.

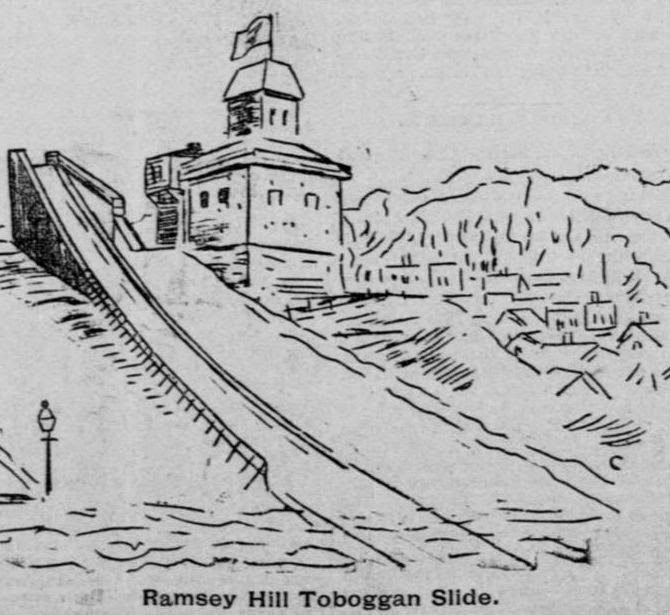

While the palace was the centerpiece of the Winter Carnival idea, it wasn’t its entirety. The city would do everything possible “to make everybody have a good time.” They would offer ice skating, tobogganing, snowshoeing, and much more. There would be ornate parties, balls, and booths and businesses of all kinds. A small admission fee, “slight on ordinary days, with an increase on days when there would be special entertainment” would be charged to help recoup costs.

Public opinion of a winter carnival was initially mixed. Some felt a carnival would be a “pleasant diversion” from the cold that would bring people from all over to see the winter splendor of Saint Paul. However, naysayers believed it was foolish to call attention to the cold winter conditions of the city. The Carnival Association pushed forward. On November 2, 1885, the St. Paul Chamber of Commerce announced that a winter festival greater than Mardi Gras would soon come to Minnesota’s capital city. No longer would there be a reason to leave the winter cold for a “land of orange blossoms.”

On December 2nd, the Winter Carnival group met to discuss the status of preparations. The excitement of the upcoming event reverberated around the city. The group had already netted $10,610 dollars toward their $12,000 dollar goal. They decided that the kickoff of the city’s inaugural winter celebration would take place on February 1, 1886. On Christmas day local newspapers advertised a “grand Carnival and Festival during the beautiful month of February.” The papers boasted that the event would take place in “the most rapidly growing and most handsome city on the continent.”

As the opening day drew near preparations were made to accommodate a large influx of spectators expected to come to the city. Officials worked with the railroads to offer affordable rates into Saint Paul during the festivities and met with various lodging houses to ensure that there were low-cost options to stay in the heart of downtown. This would give carnival-goers the financial ability to take in all the festivities. Other events took shape as well, with an ice carving contest and Masquerade Ball scheduled to take place opening night at the Ryan Hotel ice rink.

The carnival preparation continued through January and lasted until late in the night on the eve of the event. In spite of the challenges of carrying out such a grand vision (inclement weather not among them) the event was ready to go by the morning of February 1st. The Ice Palace was completed, small ice statues and arches were built and placed throughout the city, and local businesses were decorated with flags. Visitors poured into Saint Paul to take part in the history-making event.

Opening day came and “the mad carnival [was] on.” Saint Paul could now show that winter months weren’t a “perpetual night” but was instead “touched … by a sun whose brightness [was] unrivaled the world over.” As expected, people came from all directions (and climates) to take in the splendor of the Ice Palace, but the unique castle of ice was not the event’s lone success. Large crowds were found at all hours of the day taking in the sights and sounds of the city.

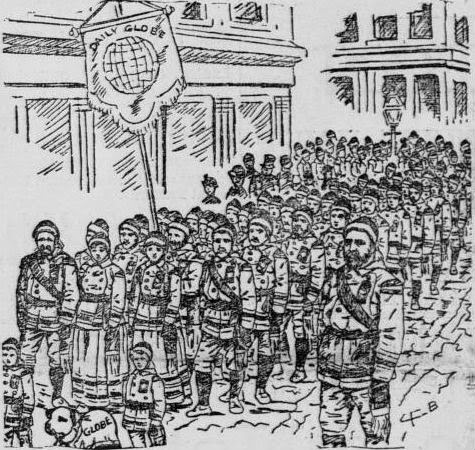

The first day saw a parade of five-thousand march down the streets of St. Paul. Excited onlookers cheered for them the entire length of their route. The night showed the beauty of winter with thousands of lights shining through a city full of intricate ice structures. The city was awake with excitement the entire opening day and remained so for the remainder of the grandiose event.

The 1886 Saint Paul Winter Carnival was an immediate success and the first of many held by the city of Saint Paul.

Works Cited:

“A Winter Carnival,” St. Paul Daily Globe, October 23, 1885. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-10-23/ed-1/seq-2/.

“The Winter Carnival,” St. Paul Daily Globe, October 28, 1885. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-10-28/ed-1/seq-2/.

“A Palace of Ice,” St. Paul Daily Globe, November 1, 1885. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-11-01/ed-1/seq-2/.

“The Winter Carnival,” St. Paul Daily Globe, November 3, 1885. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-11-03/ed-1/seq-4/.

“The Ice Carnival,” St. Paul Daily Globe, November 8, 1885. ,http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-11-08/ed-1/seq-17/.

“Central Park Selected,” St. Paul Daily Globe, December 2, 1885. ,http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-12-02/ed-1/seq-2/.

“First Grand Ice Palace and Winter Carnival at St. Paul” (Advertisement),” St. Paul Daily Globe, December 25, 1885. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1885-12-25/ed-1/seq-26/.

“The Ice Palace,” St. Paul Daily Globe, January 27, 1886. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1886-01-27/ed-1/seq-8/.

“Striking Decorations: Elaborate Arches, Ice Statues, Towers and Monuments,” St. Paul Daily Globe, February 2, 1886. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1886-02-02/ed-1/seq-1/.

“An Ice Festival: To-day’s Program,” St. Paul Daily Globe, February 3, 1886. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059522/1886-02-03/ed-1/seq-1/.

Dregni, Eric, Weird Minnesota: Your Travel Guide to Minnesota’s Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets (New York, NY: Sterling, 2006), 26.

“The Montreal Carnival (From Harper’s Magazine March 8, 1884)” Victoriana Magazine. http://www.victoriana.com/history/montrealcarnival.htm.