Dive the Florida Keys

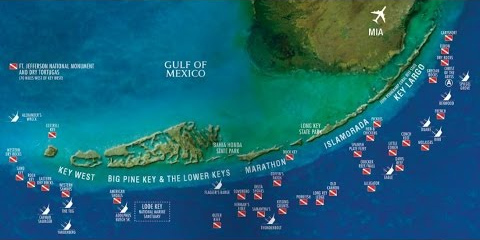

Known as the Diving Capital of the World, for its crystal clear blue waters, and fantastic underwater sea spectacles, the Florida Keys rivals the finest when it comes to scuba diving, snorkeling, and marine sightseeing.

The glistening daylight sun penetrates the shimmering seas to illuminate the brilliant and exotic marine life bantering about below. Viewers will get breathtaking glimpses of another world, as the ongoing underwater activity continues without a beat. For a more adventurous dive, faux sunlight is provided at night to transcend the pitch-black seas into a majestic and thrilling maritime slideshow.

Whether it’s the exploration of hundreds of shipwrecks, the fascination of the largest sheltered living coral reef in the continent, or the investigation of an underwater Marine Research Center, the Florida Keys offers a plethora of entertainment for divers, snorkelers, and aquatic sightseers from every caliber.

Exciting Adventures to Explore:

- Fascinating and exotic marine life

- Brilliant coral reef

- Countless shipwrecks

- Underwater Facilities, including:

- Underwater hotel

- Underwater art studio

- Underwater state park

- Underwater marine research center

- 4,000-pound bronze Christ of the Deep

The best way to explore the mysteries of the vast Florida Keys‘ water is to plan ahead. Scuba Diving in the Florida Keys isn’t particularly more difficult or dangerous than anywhere else you might dive, but a general knowledge of what to watch out for will make your dive vacation that much better if you can avoid a couple of hazards by reading about them first. You might be thinking sharks are at the top of the list, but in fact, sharks don’t pose a major risk for divers in the Florida Keys area.

Barracuda also comes to mind when you consider the dangers of diving, but the barracuda around dive spots in the Florida Keys are old hands at getting along with tourist divers. They hover around popular dive sites because some divers hand feed them little baitfish. Just stay calm and explore the reef, and the barracuda will not harm you. Below are some the elements of diving in the Keys that you do have to keep in mind:

Florida Keys Diving Hazards

Coral Cuts

Touching the coral is prohibited for environmental reasons, in other words for the protection of the coral reef, but it’s also because it poses a danger to divers as well. You can get cut on the coral, and coral has organisms in it that will almost always cause your cut to become infected. If you get cut, clean it immediately and apply antibiotic ointment to it.

Sea Lice

The culprit here is jellyfish. The larvae of thimble jellyfish to be exact. You can’t see ’em, but you’ll know they’re there if they get next to your skin: if they get under your bathing suit, you’ll feel itching, swelling, and burning sensations. Treat like you would treat a lot of common skin irritants: just put antihistamine cream on it to relieve the symptoms. Since you can’t see these microscopic organisms, all you can do know when and where they exist: Springtime and at the surface, so dive down quickly.

Stingrays

Surprise surprise, a stingray can sting! Seriously, they rarely will come after you, but divers on the bottom of the ocean can sometimes step on them and get stung by the barb at the base of the stingray’s tail, which will inject a poison that hurts like heck. Soak your bite in warm water to wear down the poison.

Fire Coral

Again, you’re not supposed to touch any coral, but you really do not want to touch Fire Coral. You won’t get cut, but you will feel burning and later incredible itching. Don’t worry, it goes away in a couple of days, but that could be the rest of your vacation. There are two varieties of fire coral: leafy and encrusting. They both have a yellow-brown color with white tips. It can wrap itself around other structures, like wrecks and other corals, both of which are places where divers are likely to go.

Florida Keys Marine Parks And Sanctuaries

Scuba diving first came onto the scene in the 1950s, and tourists began arriving in the keys to discover the beautiful treasure we have here: the coral reefs. Diving really took off as water activity, and the diving tourism started to build up. At this time, in the 1950s, there were no marine sanctuaries or parks. There just weren’t that many people bothering the coral before that point. Through the mid-1950s, both local and tourist divers enjoyed the reef here in the Florida Keys, but both groups posed a particular threat to the delicate marine ecosystem. People ripped up the coral and even used dynamite to blast it to bits, to sell in tourist shops. Fishing, too, was unregulated, and spearfishers and anglers practiced catch and keep.

John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park

In 1957 scientists and conservationists joined together and spoke up to spearhead an effort to protect marine life. One of these people was John Pennekamp, from The Miami Herald. If this name sounds familiar to you, it’s because the park that was created as a result of these conservation efforts was named after him. It’s John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, located off the shores of Key Largo.

All the marine parks and sanctuaries in the Florida Keys serve to protect the valuable natural resource here in Florida, and each has its own distinct makeup and different things to offer the diver or anyone in the waters of the Florida Keys.

Florida Keys Marine Ecology

The Florida Keys are a national treasure. Not only do these islands provide a near-tropical vacation paradise in their own back yard, but they have the reefs. The barrier reef alongside the Florida Keys is the northernmost barrier reef in the world. There is an amazing variety of marine found here, the only living coral reef in the continental USA. Living here are over forty species of coral with more than 500 types of fish swimming around it. It’s a symbiotic relationship that forms this delicate underwater life system, and some of the reefs is very very old.

Coral Polyp

The foundation of the coral reef is the coral polyp, which is the size of a mini marshmallow, at its largest, and sometimes much much smaller. These tiny polyps build the coral reef with the help of tiny algae that are called zooxanthellae. These algae, through the process of photosynthesis, take in carbon dioxide and nitrogen (which is waste from the polyp) and give out oxygen and nutrients. The polyp uses the oxygen and nutrients, and the whole process, since it is based on photosynthesis, can occur only in clear water that’s not very deep.

The zooxanthellae also somehow encourage the coral polyps to secrete calcium carbonate, and this is what makes the hard basis of the reef, the skeleton. Coral polyps also get nutrients from other sources, such as plankton that become entangled in the long fingers of the coral. These tentacle-like protrusions have little stingers on them, called nematocysts. Plankton is out mostly at night, so the coral polyps don’t bother to send out the tentacles during the day. Since they constantly need nutrients, they rely on their symbiotic relationship with the zooxanthellae to feed them during the day.

Types of Coral

There are soft corals and there are hard corals. You can tell the difference of course by touch, but you really aren’t supposed to touch coral at all. They are also different in that soft corals have eight tentacles and hard corals have six. Remember, it’s the calcium carbonate that makes the hard skeletal formation of coral, so you can logically conclude that soft coral does not produce calcium carbonate. And remember also that it’s the zooxanthellae that stimulate the production of calcium carbonate in the corals, so you might guess that soft corals are somehow not in any relationship with the zooxanthellae. That’s correct, actually. And remember about the zooxanthellae feeding the hard coral during the day, well now that you know soft coral has no symbiotic relationship with the zooxanthellae, you can also guess that soft coral doesn’t get fed during the day by the zooxanthellae. Therefore, the tentacles stay out during the day, which is perhaps why they have eight instead of six. They do double duty.

Keep these hard-working tentacles in mind when you’re out driving…they’re trying to eat, and grow, and the more they eat the more reef we have. Some of the reefs around the Florida Keys have been there since before the United States became a country. There are some areas of reef that have become famous, at least amongst divers, residents, and travelers to the Florida Keys. Maybe you’ve heard of Molasses Reef or Carysfort Reef. These are two very old reefs. To read about other reefs in the Florida Keys, check out the main Keys areas across the top of this page.

Reef Formation

Reef terminology differs from place to place, as do the reefs themselves and the varied dive experiences they afford. What some divers term a wall is likely to be called a dropoff elsewhere: standards are relative, never absolute. Since the Florida Keys are virtually devoid of dramatic walls and canyons by anyone’s standards, however, terminology characterizing deep dive destinations is largely inappropriate. Yet the broad bank which is found here supports a delicate, fragile and highly complicated reef ecosystem whose many constituents deserve close attention.

Firstly, let us consider the corals themselves. Florida’s reefs were formed 5,000 to 7,000 years ago when sea levels rose subsequent to the Wisconsin Ice Age. Their growth is painfully slow, somewhere between 0.3-0.8m (1-16 ft) every millennium. Corals survive only within certain highly constrained frameworks. The Florida Keys sustain coral growth only in areas where the minimum water temperature exceeds 70 degrees F. This rules out some of the waters surrounding the northern Keys where winter temperatures plunge below this minimum. Tidal currents also influence the delicate balance needed for coral growth. Currents flowing in from the Florida Bay may contain lethal pollutants, and even if they do not, the mere influx of freshwater may itself be harmful.

Most significant of all, humans-even in the guise of well-disposed divers constitute the single greatest threat to the reef ecosystem. We are aliens who make temporary forays into an underground environment where we do not naturally belong. As thousands, even millions of us swim, dive, anchor and explore here we exert massive cumulative influence. So if you, as an individual, truly value this fantastic underwater universe, obey one simple rule: NO TOUCHING! HANDS, BODY, FLIPPERS OFF THE REEF! At the end of your visit, let it seem as if you never visited here at all! And if it’s souvenirs your after-use your camera!

The upper area of the bank has an average breadth of between 7.4-11.1 KM (4-6 miles) throughout the Upper Keys. It may be divided into a number of regions. Near the shores, mangroves predominate except where buildings or sandy beaches replace them on the seaward reaches of many islands. In locations where mangroves extend to the water and beyond, their roots act as natural filters. Seagrasses such as turtle grass and eelgrass tend to proliferate here, too, and this tangled submarine jungle of roots and seagrass is an excellent breeding ground for many species affording superb protection for juveniles in their early days. Inshore patch reefs are small coral outcrops, often surrounded by seagrass encircled by a sandy perimeter or halo, kept clean by the grazing of nocturnal fish. Mid-channel reefs, on the other hand, are larger rock or coral formations which sometimes form spur and groove systems. These fingers of coral run from land to sea and they alternate with bands of clean sand. Mid-channel reefs are concentrated within Hawk Channel which bisects the bank along its length to constitute the major artery of internal shipping. These reefs may rise to within 4.5m (15ft) of the surface, or even break it in places, so they are generally designated by stakes or markers. Nearly all reef species are to be found here, as well as seasonal guests in the form of turtles, rays and nurse sharks roaming the channel.

Seaward of Hawk Channel, depths decrease producing offshore reefs. Although these reef patches are often smaller than their mid-channel counterparts, they boast a greater variety of coral species. Soft corals, sea fans, and sometimes even pillar corals begin to multiply. The back or landward side of the reef generally features a level expanse of sand and seagrass known as the reef flat. This region is typically protected from the turbulence of the deeper waters by a ridge of rocks and corals. The flat sandy bottom terrain here hosts conch shells and morays. Spur and grooves begin to form in the region of the fore reef. The slope moderately, their fingers growing steeper with increasing depth. Elkhorn corals are most highly developed at this point. Channels of clean sand twist between the coral fingers towards the reef crest, which may be exposed at low tide. Sand channels cascading down to the depths are called sand chutes. The slope of the reef often terminates in a flat sand pocket or sand tongue. Spurs and grooves may resume their downward course beyond this point leading ultimately to the deepest region, that of the deep reef. Corals now tend to be sparser with a low tolerance. In some places, the slope ends in a sand trench dividing the reef from another, secondary reef.

Caves, or their smaller counterparts called swim-throughs, are to be found in the fore and deep free areas. When rock formations resemble the crest of a frozen wave, you are in the presence of a ledge or overhang. These are most common at the bottom of a slope where the reef formation is at its steepest. If the formation is vertical, it is known as a wall or mini-wall-terms also applied to sheer formations along with the spurs and grooves.

The deepwater habitat, comprising depths of 90m (300ft), stretches out into the warm waters of the Gulf Stream. It houses the pelagic species including the gamefish for which Florida is famous.

On the surface of the water, you will encounter different types of buoys, the most important of which are the mooring buoys presently located only within the boundaries of the Marine Sanctuaries. Sanctuary authorities instituted the mooring buoys system and are responsible for its upkeep. The polyethylene mooring buoys have a diameter of about 46cm (18 inches) and are encoded with a letter designating their site location and a number. They are chained to the seafloor at one end, while the other bears a 5m (16.5 ft) length rope terminating in an eye splice.

How To Use The Mooring Buoys

- You are required to idle in the vicinity of a mooring buoy, keeping a careful lookout for snorkelers, swimmers, and divers.

- Always approach a buoy from downwind or down current.

- Secure your boat to the pickup lines using a length of your own rope. Snap shackles make for easy pickup and release. Larger boats are advised to give out extra lines to ensure a horizontal pull on the buoy.

- Your vessel remains your responsibility, so monitor the buoy checking to see that it is holding the vessel as required. Report any damaged buoys to Sanctuary authorities.

- If you choose not to use the mooring buoy provided, Sanctuary regulations require that you anchor in sandy areas.

The remaining red nun buoys found in open waters are intended not as moorings but as site markers numbered from east to west. Sometimes, as in the case of the Bibb and Duane wrecks, you will encounter neither official mooring buoys nor red nun markers, but buoys bearing specific designations unique to a given site.