Mexican Pottery Guide

Mexican pottery is some of the most vibrant and original artwork in the world, and it has been a part of Mexican culture for centuries. Drawing on indigenous and colonial influences, Mexican pottery has evolved to become a unique art form admired by art connoisseurs and casual observers alike.

From brightly painted “barro rojo” figurines to delicate clay vessels, there are countless popular and successful styles of Mexican pottery to explore. Here, we’ll take a closer look at several of these renowned styles, including traditional Mata Ortiz pottery, rustic Oaxacan blackware, and modern Talavera ceramics. So grab your notebook and join us as we dive into the world of Mexican pottery!

Pre-Hispanic Pottery

Mexican pottery is thought to have originated from the ancient Mayan culture which flourished in Mexico between 1000 BC and 250 AD. During this period, they developed a unique pottery-making style involving the use of both hand-molding and coil-building techniques. This early pottery was primarily used for utilitarian purposes such as storing and transporting food and liquids.

Pre-Hispanic pottery in Mexico originated from several different cultures, many of which were indigenous peoples who lived in what is now modern-day Mexico before the arrival of Europeans. The most notable cultures known for their pottery are the Aztecs, Mayas, Zapotecs, Tarascans, and Toltecs. These cultures developed complex techniques for making pieces that ranged from small figurines to large urns and sculptures, and these pieces often featured intricate decorations and designs.

Mesoamerican pottery has its roots in the cultures of the Olmecs and Mayans. These early craftsmen were producing ceramic vessels as far back as 1500 BC, making them one of the oldest known civilizations in the Americas. The development of pottery in the region is thought to have been primarily for utilitarian needs – vessels for storing food and transport vessels. However, as time passed, it became more than just a tool for everyday life; it was seen as an expression of their culture and identity.

Mesoamerican pottery was hand-coiled and low-fired, often slipped or burnished, and sometimes painted with mineral pigments. Every region developed its own pottery styles and techniques. Ceramics was used for domestic, ceremonial, funerary, and construction purposes. Mesoamerican civilizations’ pottery production was such an integral part of their culture that many techniques survived the Spanish colonization.

The craft continued to evolve during the pre-Hispanic period with a renewed emphasis on aesthetics. Potters began to create more elaborate and ornamental pieces, often decorating them with symbols, images, and colors associated with their religious beliefs and folk tales. This period saw the birth of several signature styles now widely recognized as modern Mexican pottery.

Colonial Mexican Pottery

Throughout the colony, the Spaniards introduced the potter’s wheel, the enclosed kiln, lead glazes, pigments extracted from metal oxides, and shapes such as the tile, the candle holder, and the olive jar.

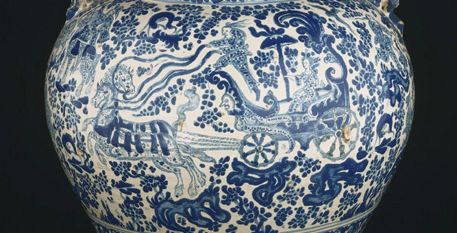

New Spain was part of the commercial route between the Philippines and Spain. Spanish galleons sailed from Manila to Acapulco full of Asian goodies, including Chinese porcelain. From Acapulco, the merchandise was carried by land to Veracruz, the main port in the Gulf of Mexico, and shipped to Spain.

Many of these goodies stayed in Mexico and significantly influenced the local artisans. Majolica ceramic production started in Puebla, is an example of this influence.

Influences on Pottery

The pottery created during this time period was heavily influenced by Spanish traditions. Pre-Hispanic methods of production were still used, but they were blended with European techniques such as tin glazing, oil painting, and slip casting. This gave the pottery an unmistakable Spanish style that blended traditional iconography with modern motifs.

Uses of Pottery

As well as being aesthetically pleasing, pottery was immensely practical during this time period. Many households kept their dinnerware and other utensils in glazed clay containers which were watertight and durable, making them perfect for everyday use. In addition, pottery vessels were used to transport goods such as food and wine, while ornaments and religious figures could be found in both secular and sacred spaces.

Symbolism in Pottery

In addition to its utilitarian purposes, pottery played an important symbolic role within colonial society. Mexican ceramics often featured native species such as birds, lizards, and reptiles which had been considered sacred in pre-Hispanic cultures. They were known to symbolize strength and protection, as well as fertility and abundance. This symbolism was used to invoke powerful images of life and death, as well as spiritual transformation and rebirth.

Contemporary Mexican Pottery

Contemporary Mexican Pottery reflects the cultural background of Mexican history. The Spanish techniques, especially the glazing, and firing; the Native shapes, colors, and patterns; the Arabic influences brought in by the Spaniards, and the colors and shapes from China, can be seen in many pottery styles throughout the country.

Handmade domestic wares have been replaced by mass-produced cheaper ceramics. In order to survive, most Mexican pottery styles have shifted to decorative pieces.

The most popular and successful Mexican pottery styles today are:

- Oaxacan Black Clay

- Multicolored Clay from Izucar de Matamoros

- Painted Clay from Guerrero

- Clay Figurines from Tlaquepaque

- Pottery from Capula

- The Majolica

- Talavera from Puebla

- Mata Ortiz Pottery

- Clay figures from Metepec

- Tonala Burnished Clay

Oaxacan Black Clay

The Black Clay (Barro Negro) from San Bartolo Coyotepec in Oaxaca had been used by Zapotecs since pre-Hispanic times, but it was Rosa Real de Nieto, aka Doña Rosa, who discovered how to give the clay its now typical shiny black color.

Black Clay (barro negro in Spanish) from Oaxaca famous for its color, sheen and unique shapes and decorative designs is made in a small village called San Bartolo Coyotepec, and although the ancient Zapotecs already used the same clay to make their pottery ware it was thanks to Rosa Real’s technique that it became world famous.

History

San Bartolo Coyotepec is a Zapotec community with a pottery tradition that goes back more than 2000 years.

The settlement was known as Zaapeche, (the place of many jaguars) by the Zapotec and after the Spanish conquest was named San Bartolome Coyotepec by Bartolome Sanchez, a conqueror awarded a local Encomienda, who built the first town,s church in 1532.

The area soils made grayish mate clay that was used by potters to make jars and dishes. For centuries no significant change in the pottery-making process was made until the early 1950s when potter Rosa Real discovered that by polishing the clay pieces before they were completely dry and lowering the firing temperature the clay changed its color to a shiny black.

The spin made by Doña Rosa turned the barro negro from Oaxaca into an international hit and soon tourists from around the world began traveling to San Bartolo Coyotepec to visit Doña Rosa’s workshop. The black clay technique spread around town and other workshops began to produce it.

Doña Rosa’s Pottery

Doña Rosa and her husband Juventino Nieto had been potters all their life; they made a living by selling mezcal holders and jars and after the successful invention of the black clay technique they created new vases, pots and candle holders designs decorated with intricate openwork flowers, leaves, and geometric forms.

Don Juventino passed away in 1978 followed by Doña Rosa in 1980. Their son Valente Nieto ran the workshop until his death in 2010. Nowadays Doña Rosa’s workshop is run by Valente’s sons.

Making Process

The color of the barro negro is the natural color of the clay found in the area. The clay is shaped in the same way the ancient Zapotec used to do it, in the Zapotec wheel, which is a disc or plate balanced over another inverted plate.

The piece is shaped by coiling or molding and then it is finished while turned on the disc. The disc with the vessel in progress is turned only with the hands so balance and skill are required.

After the pieces are shaped they are set to dry in a room, this process can take around 3 weeks. When the pieces are almost dry, the surface is lightly moistened and polished with a quartz stone.

At this stage, decorative accents such as flower drawings, intricate openwork, or small handles are added. The pieces are then fired in wood firing underground pits or above the ground kilns reaching 700°C to 800°C. These low firing temperatures produce fragile clay that can be used only for decorative purposes.

Carlomagno Pedro Martínez

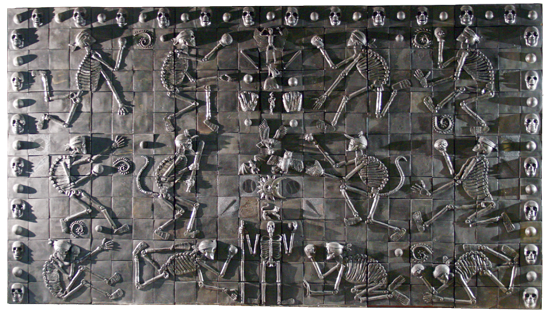

Carlomagno Pedro Martinez is a sculptor from San Bartolo Coyotepec born August 17, 1965, in a family of potters. He began sculpting figurines on black clay at a young age and at 18 he enrolled in the Rufino Tamayo Workshop in Oaxaca City. After that, he won a scholarship to study in the U.S.A. In 1996 he founded a workshop in his hometown where he teaches sculpting to children and created a new art form in Barro Negro: the clay figures.

Carlomagno sculptures are inspired by traditional Oaxaca characters, Catholic events, the Day of the Dead, and Carnivals. Every sculpture is hand coiled and unique. He has exhibited his artwork in galleries in Mexico and U.S.A.

One of his most outstanding pieces is the black clay mural called Juego en el Inframundo (Game in the Underworld) created especially for the San Bartolo Coyotepec High Performance Baseball Academy.

The mural depicts five Mixteca ball skeleton players on each side flanking 2 baseball skeleton players and a skeleton umpire in the center. On the umpire’s head lies a jaguar, the most emblematic animal in the town’s culture.

Oaxaca State Museum of Popular Arts

Another attraction on San Bartolo Coyotepec, the museum is dedicated to promoting Oaxacan artisan’s work and its cultural background. The collection includes a wide variety of barro negro pieces some of them dating from pre-Hispanic times and modern pieces made by current artisans. The museum director is sculptor Carlomagno Pedro Martínez.

Since its establishment, the museum has collected thousands of objects from all over Oaxaca including textiles, ceramics, masks, musical instruments, and carvings. It also offers educational programming through interactive displays and workshops for visitors of all ages. The museum is open Tuesday- Sunday from 10:00 am – 5:00 pm and admission is free for all. By visiting the museum, you can gain insight into the history and culture of this vibrant region and appreciate the beauty and skill of its many craftspeople.

Multicolored Clay from Izucar de Matamoros

Multicolored Clay is made in Izucar de Matamoros, Puebla which is the cradle of the popular Mexican Tree of Life sculptures; the candelabra and incense burners decorated with fine lines that almost look like filigree are the best-known items in this pottery style.

Other pieces made in the area with the same decorative style include whimsical skeletons performing different actions, assorted candlesticks, and skulls decorated with flowers and animals.

The Multicolored Clay (Barro Policromado) from Izucar de Matamoros, a small community with an extensive pottery tradition, is widely appreciated for its delicate drawings and bright colors; the town’s pottery became internationally known thanks to Alfonso Castillo Orta’s expertise and creativity. Among the most representative models in this style are the incense burners and the Tree of Life candle holders.

Multicolored Clay from Izucar History

Izucar de Matamoros is located in a fertile valley in the southeast corner of Puebla State. Its pre-Hispanic name was Itzoacan which in Nahuatl means the place of the flint. The first known inhabitants of the area were the Olmecas; 2500 years old pottery remains have been found nearby.

By the time of the Spaniards’ arrival, Itzoacan was a large city populated by Mixtecos subjugated to the Aztecs to whom they paid a cotton tribute. It had a large market and was a crossroad between many commercial routes.

Izucar was taken by the Spaniards early in the conquest and by 1521 it was given as an encomienda to Pedro de Alvarado.

The Dominicans in charge of the town’s evangelization founded a small church in 1528 and later, in 1552, Friar Juan de la Cruz began building the church and monastery of Santo Domingo de Guzman.

The monastery was finished in 1612 and became the town’s native people parish. The Spaniards had their own parochial church called Santa María de la Asunción.

Izucar developed an active religious life encouraged by the foundation of the religious Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament in 1652.

The religious activities and ceremonies together with other costumes boost the evolution of the town’s ceramic from pots and tableware to candelabra and incense burners.

The multicolored clay candelabra were used as a gift to newlyweds to ensure the couple would have many children and abundant harvests in their fields.

Incense burners are still used in the brotherhood celebrations which revolve around a silver platter that symbolizes the host. This plate is kept in each of the 14 neighborhoods of Izucar for one year.

Every month the plate is moved to one of the neighborhood houses selected to keep it. Every time the platter moves, a ceremony is held and the piece is purified with copal; the copal is burnt in a traditional incense burner and 12 incense burners are used during the year, one for each house where the plate is being guarded.

The plate changes neighborhood on Saint Peter and Saint Paul Day (June 29) known in Izucar as the day of brotherhood celebration. The platter is then taken to the Santo Domingo church where a mass is held; afterwards it is taken to the next neighborhood.

Once the plate is delivered in its new home a meal is offered. All the expenses of these celebrations are sponsored by the alms collected by the volunteers.

These traditions are at least 350 years old but the candelabra and the incense burners were not as intricately shaped and decorated as we know them today. The Izucar’s multicolored clay has evolved over the years and most of these changes happened in the second half of the past century.

Aurelio Flores (1901-1987)

The first potter that helped to the style evolution was Aurelio Flores and therefore he is considered the father of multicolored clay from Izucar.

Aurelio, a grandson of potters, began working as a child helping his parents. Born in the neighborhood of Santa Catarina Contla, Aurelio developed from the traditional candelabra and incense burners made for ceremonial purposes the sculpture known today as Tree of Life.

His colorful sculptures were decorated with leaves, flowers, and birds on their branches; Adam, Eve, and the Serpent on their main trunk and the Archangel Gabriel at their base.

For Aurelio pottery was a side job; he worked every day in his fields outside town and was a traditional healer and a musician. At first, he sold his work locally but later merchants from Puebla City came to buy his artwork that little by little became famous around the country.

Aurelio Flores son, Francisco Flores Sanchez helped him from an early age and after his passing continued making the famous sculptures in the same style which is considered now the traditional multicolored clay from Izucar.

Francisco inherited his father’s farm and his talent for music; he worked in the farm every day and was part of a Mariachi band for many years. He passed away in 2006; his children did not continue the family’s pottery tradition.

The Castillo Family

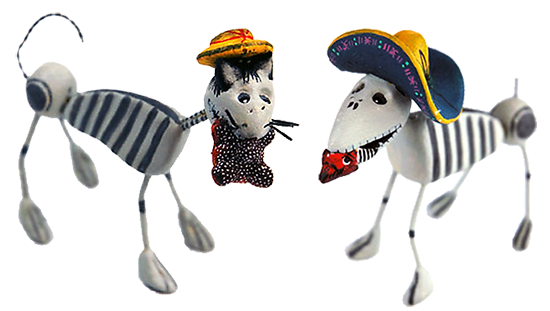

The Castillos are an extended family of potters living in the Izucar’s neighborhood of San Martin Huaquechula that began working in the 1960s and developed a new style based on the decoration of the pottery with fine lines that almost look like filigree and introduced new themes as the Day of the Dead.

The founder of the Castillo family tradition was Catalina Orta Urosa. Her parents were potters but stopped working and dedicated solely to their farm. Once married and with 6 children Catalina, remembering the techniques learned from her parents began experimenting and made Day of the Dead small figurines. She taught her children and 4 of them became potters:

Heriberto Castillo Orta

The oldest son, Heriberto specializes in mermaids, woman figurines, trees of life, and candlesticks distinct for the aged golden backgrounds behind very bold colors.

Agustin Castillo Orta

Agustin is perhaps the less famous of the siblings nevertheless he makes quality pieces decorated with family patterns.

Isabel Castillo Orta (1936-2021)

Isabel is recognized for her delicate painting and has traveled across the USA giving workshops and exhibiting her artwork. Among her notable pieces are Trees of Life, Day of the Dead candelabra, and Virgin of Guadalupe-themed pieces.

Isabel ran her workshop with the help of her children and grandchildren. Among them, grandsons Gregorio and Giovanni Mercado Morgan have begun making pieces on their own. Their mother, Virginia Morgan Tepetla, makes trees of life, catrinas, and Guadalupe Virgin figures.

Alfonso Castillo Orta

Considered a Master by the Banamex Foundation and winner of the 1996 National Prize of Folk Art Alfonso Castillo was the most prominent artist in Izucar. His domain of both clay sculpting and painting put his artwork on a different level.

His pieces have been collected by museums in Mexico, the USA, Canada, and Europe. Alfonso passed away in 2009 but his wife Marta and their children Veronica, Alfonso, Marco, Martha and Patricia Castillo Hernandez are still working.

Casa Balbuena and Arte Casbal

Maria Luisa Balbuena Palacios was married to Heriberto Castillo Orta and together they ran a workshop named Itzoacan until their marriage ended. Maria then founded Casa Balbuena; she makes a great variety of pieces including large tree of life and miniature animal candle holders.

Maria and Heriberto youngest sons, Jorge and Ulises Castillo Balbuena began working on their own in 2004 naming their workshop Arte CasBal and are for sure keeping up with their parents’ work.

Tomas Hernandez Baez

Tomas is the brother of Martha Hernandez, Alfonso Castillo’s wife; he began working in their workshop and later became independent. He is a very talented clay sculptor and his painting is fine and detailed; he developed his own style and specializes in Day of the Dead figures.

Multicolored Clay-Making Process

Making a multicolored clay figure can take a few days or several weeks depending on the size and complexity of the piece.

The clay which comes in clods is hit with a mallet until pulverized and afterwards sifted in a sieve until powdered. The leftovers are set in a water pond to rot for about a week.

In a working table where the powdered clay has been arranged the mud that was previously sifted is added little by little mixing them both together. The mix is then cut into 8-pound balls and kneaded until it feels like dough. The balls of clay are stored and covered with a wet cloth to prevent them from drying.

The clay is then ready to be sculpted; most pieces are hand coiled with a few exceptions like flowers and leaves that are sometimes made with molds. When the sculptures are done they are left to dry which can take a few hours for a small piece or a few days for a larger one. Once dried the pieces are taken to the kiln where they will be fired for around 6 hours at 850°C (1560° Fahrenheit).

The pieces are left to cool down in the kiln for about 16 hours; once out of the kiln, they are polished to smooth their surface and painted with a coat of white acrylic paint.

At last, the pieces are ready to be decorated with the traditional bold colors and fine motifs that characterize the multicolored clay from Izucar. Acrylic paintings are the choice of every artist. After being decorated the piece is coated with furniture varnish to avoid the colors from fading.

Painted Clay from Guerrero

Nahuatl folk painting can be fully appreciated in the Barro Pintado colorful birds, flowers, landscapes, and everyday town activities. Boxes, plates, and animal figurines portray the Mezcala people’s stories and costumes.

Painted Clay Barro Pintado is made by Nahuatl painters from La Mezcala, a region on the Balsas River basin in Guerrero State. The pottery features animals, boxes, plates and bowls beautifully painted with colorful birds, deer, flowers, and scenes that represent the artists’ life and culture.

History

Pottery production in Oapan and Ameyaltepec dates from pre-Hispanic times. Women made pots and plates, ceremonial pieces, and human and animal figures used as toys.

In the 1950s foreign tourism began coming to Mexico; Taxco, Acapulco, and Cuernavaca became outlets for the Balsas crafters. Soon painting styles became colorful, and decorative, featuring fantasy animal figures, some nonrealistic humans, and plenty of floral and geometric designs.

In 1962 the use of Amate paper changed the Mezcala folk painting. Artisans became chroniclers of their culture representing their life and traditions on their artwork.

The painting style developed by Amate painters was soon used in pottery. Religious and cultural events; farming, fishing, hunting, and crafting scenes filled the pots, plates, and boxes in a style known as pottery with stories or barro con historia. The Balsas folk artists became internationally known for their paintings. In a few years, artisans looking for new styles began painting wooden fish and rabbits.

Painted Clay-Making Process

As in everything else in these communities, the whole family takes a share in making a barro pintado piece.

Most of the pottery used by the Balsas painters comes from Tuliman one of the villages in the region. The clay pieces are shaped with molds, fired on wood firing kilns, and sanded.

Sometimes the clay piece is white-coated first. Next, the piece is drawn with a pencil. The drawing is filled with acrylic paintings. When the paint has dried the piece is varnished with an acrylic lacquer.

Craft making is alternated with harvesting, livestock grazing, domestic work, and town celebrations.

Different Styles

The Barro Pintado just like the Amate paper paintings has two main painting styles. Some pottery is painted with flowers, birds, deer, and rabbit while other is decorated with community celebrations or everyday activities.

Important Villages in the Mezcala

There are several villages in the area that paint on clay, amate or wood, but for their geographic location or their historical background these are considered special in the painted clay development as a folk art style:

- Oapan has a pre-Hispanic pottery tradition and was the first place where painted clay was made.

- Ameyaltepec is the hometown of Pedro de Jesus and Cristino Flores Medina pioneers in the Amate paintings. The biggest evolution in the painting style was accomplished there.

- Xalitla a small village located next to the federal highway from Mexico City to Acapulco, became a producing and selling center for many Guerrero folk art styles.

Clay Figurines from Tlaquepaque

At the beginning of the 20th Century, Pantaleon Panduro revolutionized Tlaquepaque’s pottery-making with his incredible sculpting talent. This village near Guadalajara has a clay working heritage dating back to prehispanic times.

Pantaleon became internationally known for his clay busts and figurines and created a tradition that lasts till today. With their clay effigies and nativity scenes, Panduro and his descendants enriched Tlaquepaque’s pottery heritage.

Clay figuirines from Tlaquepaque can be found depicting both everyday people, significant historical figures, or religious icons. Many also feature intricate floral motifs, bold colors, and detailed designs. The clay figurines are created by mixing together ocher, black lead, quartz sand, and various rocks, which are then hand molded into their desired shape. Once dried and hardened, they are decorated with paint made from minerals and natural pigments like gold, silver, and copper, ensuring that no two pieces are ever exactly the same.

Pottery from Capula

Capula is a small village in Michoacan state with a pre-Hispanic pottery tradition. Clay tableware delicately decorated with flowers and fishes, kitchen plates painted with the town’s unique dotting style and most recently clay Catrinas award Capula Pottery international reputation.

Captivating and unique, pottery from the small Mexican town of Capula is sure to take your breath away! Handcrafted by local artisans in vibrant hues and eye-catching designs, this stunning pottery embodies the rich culture and spirit of the region. From traditional Talavera pots with intricate geometric patterns to colorful earthenware dishes adorned with whimsical floral designs, pieces from Capula are sure to brighten up any space.

The Majolica

Mexican majolica pottery was first made in Puebla in the 16th Century spreading later to Guanajuato and Aguascalientes. Nowadays the most recognized Majolica workshops are “Gorky Gonzalez”, “Capelo” and “Ceramica Santa Rosa”.

Mexican majolica pottery has a long, storied history that dates all the way back to the days of the Aztecs. This type of pottery is known for its brightly colored glazes and intricate designs, which often depict scenes from nature or folkloric characters. The traditional technique used to make Mexican majolica pottery involves layering clay, coating it with colorful glazes, and then baking it in an oven. This time-honored craft is still practiced today by talented artisans who continue to bring these vibrant pieces to life.

Talavera from Puebla

Talavera de Puebla is a majolica-style pottery made in Puebla with the same techniques used in Colonial times. Talavera brand is reserved by law for this earthenware. Two legitimate Talavera workshops are “Talavera Uriarte” which keeps with the traditional designs and “Talavera de la Reyna” sought after for its contemporary styles.

This unique style of ceramic pottery originated in the Mexican state of Puebla in the 15th century and has become renowned worldwide for its intricate designs, bright colors, and precise details. The pieces are typically handcrafted and painted with colorful glazes, giving each item a one-of-a-kind look that is truly stunning. Within this art form, one can find everything from elaborately decorated plates and vases to more rustic items such as flower pots and animal figures.

The craftsmanship involved in creating these pieces is truly impressive, as it often requires artisans to use multiple techniques, including throwing, shaping, and sculpting. Additionally, it can take several days to complete a single piece of pottery due to the highly detailed nature of the process. In order to achieve the high levels of quality associated with Talavera from Puebla, artisans must fire their pieces at very high temperatures for a prolonged period of time.

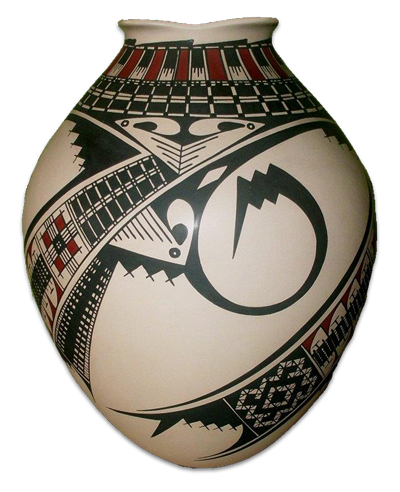

Mata Ortiz Pottery

Mata Ortiz, a small town located near the remains of the ancient city of Paquime, has become internationally recognized thanks to its ceramic production. Artisans from the village, located in Chihuahua state, have successfully reproduced the delicate hand-coiled and elegantly painted vases and bowls made by the unknown early inhabitants of Paquime.

Mata Ortiz Pottery is created through an intense labor of love, with each piece crafted by hand using traditional techniques that have been honed over generations. The clay used for the pieces is collected from the local riverbeds and mixed with natural materials like mica and quartz, giving it strength and durability that is both beautiful and unique. Once fired, a layer of mineral-based pigment is added before being polished off with a smooth sheen finish. With its distinctive style rooted in ancient practices, Mata Ortiz Pottery has become one of the most sought-after art forms in Mexico and around the world.

Clay figures from Metepec

In Metepec, a town in the Toluca Valley, pottery-making is a tradition since pre-Colonial times. They specialized in, sun faces, and green tableware until 1940 when Modesta Fernández Mata began making the Tree of Life. Today Metepec is internationally known for these sculptures and Modesta’s descendants, the Soteno family, have been repeatedly awarded for their incredibly detailed creations.

The practice of crafting clay figures dates back hundreds of years, with evidence of terracotta figurines found as far back as the 12th century. It has since become a hugely popular local tradition, with many families in Metepec passing down the craft across generations. Today, the figures are widely sought after among tourists visiting Mexico as they make for great souvenirs and gifts.

Tonala Burnished Clay

This clay style from Tonala includes necked jugs decorated with twisted animals, such as rabbits, birds, and cats. Frequent color combinations include delicate tones of rose, gray-blue, and white on a background of brown, light gray, green, or blue. The Barro Bruñido pieces are rubbed with a rock until their surface is so polished it looks as if they were glazed.

Tonala burnished clay is a unique ceramic art form that has its origins in the Jalisco region of Mexico. The craft dates back to an ancient tradition of pottery-making practiced by the indigenous Toltec and Chichimeca cultures in this area. The art’s signature style consists of hand-crafted, burnished earthenware vessels covered with beautiful organic patterns and geometric shapes. The process begins with the ceramist creating a wheel-thrown clay shape, which is then polished to a glossy finish using natural materials such as stones, corncob husks, or leather pouches filled with pebbles.

The clay used for burnished pieces has artisans shaping and reworking until it reaches a thinness of around 10 millimeters or less. This requires considerable skill and experience, but it is worth the effort to create pieces with vibrant colors, strong lines, and a smooth sheen. Additionally, the clay can be dyed and glazed to impart unique shades and textures.