30 Best Beautiful French Beaches 2024

With over 2,000 miles of coastline, France has plenty of space for beaches. With access to the English Channel, the Bay of Biscay, and the massive Mediterranean Sea, France has some of Europe’s best beaches.

France has a diverse landscape and a changing climate. As a result, it has a variety of shorelines. This, in turn, provides a diverse range of beaches. As a result, France is an ideal European beach destination.

Here are France’s most beautiful beaches, with something for everyone, from big sandy beaches on the Atlantic Coast to luxurious beach resorts along the French Riviera, Corsican wonders, and a plethora of fascinating geological formations.

Anglet (Angelu) Beach

Immediately north of Biarritz, Anglet sprawls up the coast from the Pointe St-Martin to the mouth of the Adour.

There is nothing to see except for two superb beaches – the Chambre d’Amour, so named for two lovers trapped in their trysting place by the tide, and the Sables d’Or, much favored by the surfers and with boards for rent. Here, too, swimming is very dangerous, so do heed the warning signs.

You can catch a #6 or #9 bus here from the central stops in Biarritz, or walk the distance in about thirty minutes, along avenue de l’Imperatrice, avenue MacCroskey, then second left down to the seaside boulevard des Plages.

Antibes

Antibes, or rather its promontory the Cap d’Antibes, is one of the select places on the Cote d’Azur where the really rich and the very, very successful still live, or at least have residences.

Yet it’s not immediately obvious why this area should be so desirable: it’s just as built-up as the rest of the Riviera, with no open countryside separating Golfe Juan, Juan-les-Pins, and Antibes.

Long-time resident Graham Greene said it was the only town on the Cote that hadn’t lost its soul; perhaps he was right, though he also gave his reason for living there as simply to be with the woman he loved.

Be that as it may, Antibes is extremely animated, has one of the finest markets on the coast and the best Picasso collection in its ancient seafront castle; and the southern end of the Cap still has its woods of pine, in which the most exclusive mansions hide.

Plage de la Salis, the longest Antibes beach, runs along the eastern neck of Cap d’Antibes, with no big hotels owning mattress exploitation rights – an amazing rarity on the Riviera.

To the south, at the top of Chemin du Calvaire, you can get superb views from the Eglise de la Garoupe (July & Aug 10am-noon & 2:30-6 pm; rest of year 9:30am-noon & 2:30-5 pm), which contains Russian spoils from the Crimean War and hundreds of ex-votos.

To the west, on boulevard du Cap between Chemins du Tamisier and G.-Raymond, you can wander around the Jardin Thuret (Mon-Fri 8:30am-noon & 2:30-5:30 pm; free), botanical gardens belonging to a national research institute.

Back on the east shore, further south, a second beach, plage de la Garoupe, now heavily colonized by sun beds, is linked by a footpath to the peninsula’s southern tip.

There are more sandy coves and little harbors along the western shore, where you’ll also find the Musee Naval et Napoleonien (Mon-Fri 9:30am-noon & 2:15-6 pm, Sat 9:30am-noon; closed Oct), at the end of avenue J.-F.-Kennedy.

This documents the great return from Elba along with the usual Bonaparte paraphernalia of hats, cockades, and signed commands.

Audierne

Though on the whole, the exposed southwestern extremities of Brittany are not areas you’d immediately associate with a classic summer sun-and-sand holiday, Audierne, 25km west of Douarnenez on the Bay of Audierne, is an exception.

An active fishing port, specializing in prawns and crayfish, it spreads along the northern shore of the Goyen estuary a short way back from the sea.

From the town center, the road continues just over 1km to the long, curving, and surprisingly sheltered beach of Ste-Evette.

Bandol

Across La Ciotat bay are the fine sand beaches and unremarkable family resort of Les Lecques, an offshoot of the old town of St-Cyr-Sur-Mer, behind.

The train station is in St-Cyr, but the tourist office is on the place de l’Appel du 18 Juin, on the seafront in Les Lecques.

St-Cyr has the cheapest accommodation, such as the rather basic but serviceable Auberge Le Clos Fleurie, near the station on avenue General-de-Gaulle, but there’s a greater choice in Les Lecques.

A ten-kilometer coastal path (signposted in yellow) runs from the east end of Les Lecques’ beach through a rare villa-free stretch of secluded beaches and Calanques to the unpretentious resort of Bandol, while inland is vineyards producing some of the best wines on the Cote, the appellation Bandol.

The appellation covers a large area stretching from St-Cyr to Le Castellet up in the hills to the edge of Ollioules, just east of Toulon; you’ll see degustation signs along the route.

The reds are the most reputed, maturing for over ten years on a good harvest, with bouquets sliding between pepper, cinnamon, vanilla, and black cherries.

Brittany’s Abers

The coast west of Roscoff is some of the most dramatic in Brittany, a jagged series of abers – deep, narrow estuaries – in the midst of which are clustered small, isolated resorts. It’s a little on the bracing side, especially if you’re making use of the numerous campsites, but that just has to be counted as part of the appeal. In summer, at least, the temperatures are mild enough, and things get progressively more sheltered as you move around towards Le Conquet and Brest.

If you’re dependent on public transport, bear in mind that the only stop on the Roscoff-Brest bus before it turns inland is Plouescat. It is not quite on the sea itself, but there are campsites nearby on each of three adjacent beaches; of the hotels, the best value is the Roc’h-Ar-Mor, right on the beach at Porsmeur.

Brignogan-Plage, on the next aber , has a small natural harbor, once the lair of wreckers, with beaches and weather-beaten rocks to either side, as well as its own menhir.

The aber between Plouguerneau and L’aber-Wrac’h has a stepping-stone crossing just upstream from the bridge at Llanelli’s, built in Gallo-Roman times, and its long-cut stones still cross the three channels of water (access off the D28 signposted “Rascoll”), and continue past farm buildings to the right to “Pont du Diable”. L’Aber-Wrac’h itself is a promising place to spend a little time. It’s an attractive, modest-sized resort, within easy reach of a whole range of sandy beaches and a couple of worthwhile excursions.

At the small harbor of Portsall, 5km along the coast from the far side of the next aber , l’Aber-Benoit, the Espace Amoco Cadiz commemorates a defining moment in local history (daily 9.30 am-1 pm & 2.30-7 pm; free): on March 17, 1978, the sinking of the Amoco Cadiz supertanker resulted in an oil spill that devastated 350km of the Breton coastline, and threatened to ruin the local economy.

Five kilometres west of Portsall is Tremazan, whose ruined castle was the point of arrival in Brittany for Tristan and Iseult. From here a beautiful corniche road leads further along the coast. Odd little chapels dot the route, and the views of sea and rocks are unhindered before turning inland just before Le Conquet.

Benodet

Once out of its city channel, the Odet takes on the shape of most Breton inlets, spreading out to lake proportions and then turning narrow corners between gorges.

The family resort of Benodet at the mouth of the river (reachable by boat from Quimper ) has a long sheltered beach on the ocean side, with amusements for children and beachside nurseries.

Among the nicest hotels in Benodet are the Hotel-Restaurant Le Minaret, an odd-looking building in a superb seafront position on the corniche de l’Estuaire, and the Bains de Mer , 11 rue du Kerguelen. Benodet also has several large campsites – if anything, rather too many of them – such as the enormous four-star du Letty, southeast of the village by plage du Letty on rue du Canvez (closed early Sept to mid-June).

The coast that continues east of Bйnodet is rocky and repeatedly cut by deep valleys. It suffered heavily in the hurricane of 1987, but the small resort of Begmeil survives, albeit with fewer trees to protect its vast expanse of dunes. These are ideal for campers, with several official sites, and just back from the seafront, there’s also the hotel Thalamot.

Around the Foret-Fouesnant in particular, 12km east of Bйnodet, the hills are much too steep for cyclists to climb, and forbidden to heavy vehicles such as caravans. The Forкt-Fouesnant minor road may look good, but there are few beaches or places to stop. Motorists would do best to take the more direct D44, a few kilometers inland, followed by the D783, which leads close to the major towns along the route.

Bormes-Les-Mimosas

Seventeen kilometers east of Hyeres, Bormes-Les-Mimosas, like all good Provencal villages, is indisputably medieval in flavor, with a ruined but restored castle at the summit of its hill, protected by spiraling lines of pantiled houses backing onto short-cut flights of steps.

The mimosas here, and all along the Cote d’Azur, are no more indigenous than the people passing in their Porsches: the tree was introduced from Mexico in the 1860s, but the town still has some of the most luscious climbing flowers of any Cote town.

To the southwest of Bormes is one of those rare unbuilt-up stretches of coast around Bregancon and Cabasson, good wine-growing terrain, harboring a presidential residence in the castle at Cap de Bregancon. Unfortunately, access to the sea is heavily controlled, with three beaches charging hefty parking fees (and a small charge for pedestrians and cyclists). The beach by the castle past Cabasson is the best.

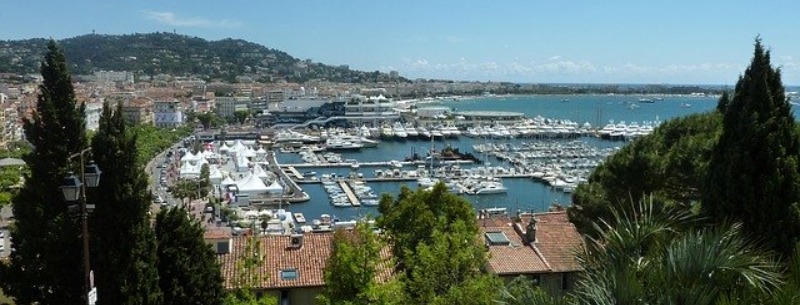

Cannes

The film industry and all other manners of business junketing represent CANNES ‘s main source of income in an ever-multiplying calendar of festivals, conferences, tournaments, and trade shows.

You’ll find non-paying beaches to the west of Le Suquet, along the plages du Midi, and just east of the Palais des Festivals. But the sight to see is La Croisette, the long boulevard along the seafront, with its palace hotels on one side and private beaches on the other. It is possible to find your way down to the beach without paying, but not easy (you can of course walk along it below the rows of sun beds).

The Cannes beaches, owned by the deluxe Palais-hotels – the Majestic, Carlton, and Noga Hilton – are where you’re most likely to spot a face familiar in celluloid or a topless hopeful, especially during the film festival, though you’ll be lucky to see further than the sweating backs of the paparazzi.

At the quays at the end of La Croisette and the Vieux Port, you’ll find millionaires eating their meals served by the white-frocked crew on their yacht decks, feigning oblivion of land borne spectators a crumb’s flick away.

As an alternative to the dubious entertainment of watching langoustines disappear down overfed mouths, you can buy your own food in the Forville covered market two blocks behind the Mairie, or wander through the day’s flower shipments on the allйes de la Libertй, just back from the Vieux Port.

Cap d’Agde

Cap d’Agde, lies to the south of Mont St-Loup, 7km from Agde.

The largest (and by far the most successful) of the new resorts, it sprawls laterally from the volcanic mound of St-Loup in an excess of pseudo-traditional modern buildings that offer every type of facility and entertainment – all expensive.

It is perhaps best known for its colossal quartier naturiste, one of the largest in France, with the best of the beaches, space for 20,000 visitors, and its own restaurants, banks, post offices, and shops. Access is possible, though expensive if you’re not actually staying there.

Cassis Beach Resort

A lot of people rate Cassis the best resort on this side of St-Tropez – its inhabitants most of all. Hemmed in by high white cliffs, its modern development has been limited to a model toytown on the steep inclines above the port. Portside posing and drinking aside, there’s not much to do except sunbathe and look up at the ruins of the town’s medieval castle, built in 1381 and refurbished by Monsieur Michelin, the authoritarian boss of the family tyres and guides firm.

The favored lazy pastime, though, is to take a boat trip to the Calanques – long, narrow, deep fjord-like inlets that have cut into the limestone cliffs. Several companies operate from the port but check if they let you off or just tour in and out, and be prepared for rough seas.

If you’re feeling energetic, you can take the well-marked footpath from the route des Calanques behind the western beach; it’s about ninety minutes walk to the furthest and best calanque, En Vau, where you can climb down rocks to the shore. Intrepid pine trees find root-holds, and sunbathers find ledges on the chaotic white cliffs. The water is deep blue and swimming between the vertical cliffs is an experience not to be missed.

Les Sports Loisirs Nautiques rents out windsurfing and watersports equipment by the beach next to the port.

Corsica Beaches

Every year, over a million people visit Corsica, drawn by its mild climate even in winter and some of Europe’s most astonishingly diverse landscapes.

There are no finer beaches in the Mediterranean than Corsica’s perfect half-moon bays of white sand and clear water, or seascapes more inspiring than the west coast’s granite cliffs.

Despite the fact that the annual influx of tourists now outnumbers the island’s population by a factor of seven, tourism has not ruined the place: there are a few resorts, but overdevelopment is rare, and high-rise blocks are limited to the main towns.

Cote d’Emeraude

To the west of the Rance, beyond Dinard, begins the green of the Cote d’Emeraude . Though composed mainly of developed family resorts, it also offers wonderful camping, at its best around the heather-backed beaches near Cap Frehel, a high, warm expanse of heath and cliffs with views extending on good days as far as Jersey and the Ile de Brehat – camping is, however, forbidden within 5km of the headland itself.

The Fort la Latte, to the east, is used regularly as a film set. Its tower, containing a cannonball factory, is accessible only over two drawbridges and offers good views.

The perfect crescent of beach at Erquy curves through more than 180 degrees. At low tide, the sea disappears way beyond the harbor entrance, leaving gentle ripples of paddling sand. Equipped with suitable boots, you can walk right across its mouth, from the grassy wooded headland on the left side over to the picturesque little lighthouse at the end of the jetty on the right.

The huge beach in the broader bay of Le Val-Andre to the west is of finer, sweeter-smelling sand, and the endless pedestrian promenade that stretches along the seafront feels oddly Victorian, consisting solely of huge old houses undisturbed by shops or bars. However, Le Val-Andrй is definitely more of a town than Erquy, and rue A-Charner, running parallel to the sea one street back, is busy with holiday-makers in summer.

D-Day Beaches

Despite the best efforts of Stephen Spielberg, it is all but impossible now to picture the scene at dawn on D-Day, June 6, 1944, when Allied troops landed along the Norman coast between the mouth of the Orne and Les Dunes de Varneville on the Cotentin Peninsula.

For the most part, these are innocuous beaches backed by gentle dunes, and yet this foothold in Europe was won at the cost of 100,000 soldiers’ lives. That the invasion happened here, and not nearer to Germany, was partly due to the failure of the Canadian raid on Dieppe in 1942.

The ensuing Battle of Normandy killed thousands of civilians and reduced nearly six hundred towns and villages to rubble but, within a week of its eventual conclusion, Paris was liberated.

The beaches are still often referred to by their wartime code names: Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah. Substantial traces of the fighting are rare, the most remarkable being the remains of the astounding Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches, 10km northeast of Bayeux.

Further west, at Pointe du Hoc on Omaha Beach, the cliff heights are still deeply pitted with German bunkers and shell holes, while the church at Ste-Mere-Eglise, from which the US paratrooper who became entangled in the steeple dangled during heavy fighting throughout The Longest Day, still stands, and now has a model parachute permanently fastened to the roof.

Douarnenez

Sufficient quantities of tuna, sardines and assorted crustaceans are still landed at the port of Douarnenez , in the superbly sheltered Baie de Douarnenez, south of the Crozon peninsula, to keep the largest fish canneries in Europe busy.

Since 1993, Port-Rhu, on the west side of town, has been designated as the Port-Musee, with its entire waterfront taken up with fishing and other vessels gathered from throughout northern Europe. Its centerpiece, the Musee du Bateau in the place de l’Enfer, doubles as a working boatyard, where visitors can watch or join in the construction of seagoing vessels, using techniques from all over the world and from all different periods.

Of the three separate harbor areas in Douarnenez, the most appealing is the rough-and-ready port de Rosmeur, on the east side, which is nominally the fishing port used by the smaller local craft. Its quayside – far from totally commercialized, but holding a reasonable number of cafes and restaurants – curves between a pristine wooded promontory to the right and the fish canneries to the left, which continue around the north of the headland.

The various beaches around town look pretty enough, but they are dangerous for swimming.

Houat And Hoedic

The islands of Houat and Hoedic can also be reached by ferry from Quiberon-Port-Maria with the Societe Morbihannaise et Nantaise de Navigation (1-7 sailings daily depending on the season). The crossing to Houat takes forty minutes, to Hoedic another 25. Navix run day-trips to Houat only from Vannes, Port Navalo and La Trinite daily in July and August.

You can’t take your car to these two very much smaller versions of Belle-Ile. Both have a feeling of being left behind by the passing centuries, although the younger fishermen of Houat have revived the island’s fortunes by establishing a successful fishing co-operative.

Houat in particular has excellent beaches – as ever on its sheltered (eastern) side – that fill up with campers in the summer even though camping is not strictly legal.

Hoedic on the other hand has a large municipal campsite. There are a couple of small hotels on Houat – L’Ezenn and the pricier Hotel-Restaurant des Iles – and one on Hoedic, Les Cardinaux.

Hyeres Beaches

The charming seaside resort on the French Riviera sprawls over several dozen kilometers of sumptuous coastline. Explore Hyères’ most beautiful beaches, from the peninsula of Giens to the Golden Islands, and to enjoy the beautiful view and water activities.

Beautiful beaches can be found on Porquerolles Island, near Hyeres and Toulon in the south of France. The beaches of the Golden Islands, which are only a few minutes by boat from the coast, are among the best in France. Here are some of our favorite beaches, but there are so many hidden creeks and intimate coves that we’re sure you’ll find your own favorites as well.

Best Beaches Hyeres, Porquerolles & Golden Islands

Ile de Re Beach

A half-hour drive west from La Rochelle, the Ile de Re is a low, narrow island some 30km long, fringed by sandy beaches to the southwest and salt marshes and oyster beds to the northeast, with the interior a motley mix of small-scale vine, asparagus and wheat cultivation.

All the buildings on Re are restricted to two stories and are required to incorporate the typical local features of whitewashed walls, curly orange tiles and green-painted shutters, which give the island villages a southerly holiday atmosphere.

Out of season the island has a slow, misty charm, and life in its little ports revolves exclusively around the cultivation of oysters and mussels. In season, though, it’s extraordinarily crowded, with upwards of 400,000 visitors passing through.

The crowds mainly head for the southern beaches; those to the northeast are covered in rocks and seaweed, and the sea is too shallow for bathing.

La Baule

There is something very surreal about emerging from the Briиre to the coast at La Baule – an imposing, moneyed landscape where the dunes are no longer bonded together with scrub and pines, but with massive apartment buildings and luxury hotels.

Sited on the long stretch of dunes that links the former island of Le Croisic to the mainland, it owes its existence to a storm in 1779 that engulfed the old town of Escoublac in silt from the Loire, and thereby created a wonderful crescent of sandy beach.

Neither La Baule’s permanence nor its affluence seems in any doubt these days. It is a resort that very firmly imagines itself in the south of France: around the crab-shaped bay, bronzed nymphettes and would-be Clint Eastwoods ride across the sands into the sunset against a backdrop of cruising lifeguards, horse-dung removers and fantastically priced cocktails.

It can be fun if you feel like a break from the more subdued Breton attractions – and the beach is undeniably impressive. It’s not a place to imagine you’re going to enjoy strolling around in search of hidden charms; the back streets have an oddly rural feel, but hold nothing of any interest.

La Ciotat

You might not associate the building of 300,000-tonne oil and gas tankers with the pleasures of a Mediterranean resort. But it is one of the surprising charms of La Ciotat that the Vieux Port, below a golden stone old town, shelters the dramatic massive cranes and derricks of the former shipyards as well as the fishing fleet and the odd yacht or two.

La Ciotat is not a town for keyed-up museum or monument motivation. It’s a relaxing place with excellent beaches to loaf on and little glamour glitter.

Le Conquet

Le Conquet at the far western tip of Brittany, 24km beyond Brest, is a wonderful place, scarcely developed, with a long beach of clean white sand, protected from the winds by the narrow spit of the Kermorvan peninsula.

It is very much a working fishing village, with grey-stone houses leading down to the stone jetties of a cramped harbor. It occasionally floods, by the way, causing great amusement to locals who watch the waves wash over cars left there by tourists taking the ferry out to Ouessant and Molиne.

A good walk 5km south brings you to the lighthouse at Pointe St-Mathieu, looking out to the islands from its site among the ruins of a Benedictine abbey. A small exhibition explains the abbey’s history, including the legend that it holds the skull of St Matthew, brought here from Ethiopia by local seafarers.

Locquirec

Locquirec , across the bay from Lannion, manages to have beaches on both sides, without ever quite being thin enough to be a real peninsula.

Around the main port, smart houses stand in sloping gardens, looking very southern English with their whitewashed stone panels, grey slate roofs and jutting turreted windows.

On the last Sunday in July, Locquirec holds a combined pardon de St Jacques and Festival of the Sea. Locquirec veers dangerously close to being over-twee, and none of its hotels is all that cheap – although the Grand Hotel des Bains , 15 rue de l’Eglise has so gorgeous a setting that perhaps it doesn’t matter.

The Sables-Blancs, 25 rue des Sables-Blancs, offers sea views at considerably lower prices, while the municipal campsite, the Toul ar Goue, 1km south along the corniche, is beautifully positioned, too.

Malo-les-Bains Beach

Malo-les-Bains is a more attractive place to stop off than Dunkerque: it’s a surprisingly pleasant nineteenth-century seaside suburb on the east side of town (bus #3 & #9), from whose vast sandy beach the Allied troops embarked in 1940 .

Digue des Allies is the dirtier end of an extensive beachfront promenade lined with cafes and restaurants; at the cleaner end, Digue des Mers, the beach can almost seem pleasant when the sun comes out – that is, if you avert your eyes from the industrial inferno to the west.

However, the suburb actually reveals its fin-de-siecle charm away from the seafront, a few parallel blocks inland along avenue Faidherbe and its continuation avenue Kleber, with the pretty green place Turenne sandwiched in between; around here you’ll find some excellent patisseries, boulangeries and charcuteries.

Marseille

Marseille is divided into sixteen arrondissements which spiral out from the focal point of the city, the Vieux Port. Due north lies the old town, Le Panier, site of the original Greek settlement of Massalia.

The most popular stretch of sand close to the city centre is the plage des Catalans, a few blocks south of the Palais du Pharo. This marks the beginning of Marseille’s corniche, avenue J.-F.-Kennedy, which follows the cliffs past the dramatic statue and arch that frames the setting sun of the Monument aux Morts des Orients.

South of the monument, steps lead down to an inlet, Anse des Auffes, which is the nearest Marseille gets to being picturesque. Small fishing boats are beached on the rocks, the dominant sound is the sea, and narrow stairways and lanes lead nowhere.

The corniche then turns inland, bypassing the Malmousque peninsula, whose coastal path gives access to tiny bays and beaches – perfect for swimming when the mistral wind is not inciting the waves. You can see along the coast as far as Cap Croisette and, out to sea, the abandoned monastery on the Оles d’Endoume and the Chвteau d’If .

The corniche ends at the Plage du Prado, the city’s main sand beach, where the water is remarkably clean. A short way up avenue du Prado, avenue du Park-Borely leads into the city’s best green space, the Parc Borely, with a boating lake, rose gardens, palm trees and a botanical garden (daily 8am-9pm; free).

The quickest way to the park and the beaches is by bus #19, #72 or #83 from Mє Rd-Pt-du-Prado; for the corniche, take bus #83 from the Vieux Port.

Nice Beaches

The capital of the Riviera and fifth largest city in France, Nice scarcely deserves its glittering reputation.

Living off inflated property values and fat business accounts, its ruling class has hardly evolved from the eighteenth-century Russian and English aristocrats who first built their mansions here; today it’s the rentiers and retired people of various nationalities whose dividends and pensions give the city its startlingly high ratio of per capita income to economic activity.

The point where the Paillon flows into the sea marks the beginning of the world-famous palm-fringed promenade des Anglais, created by nineteenth-century English residents for their afternoon’s sea-breeze stroll along the Mediterranean sea coast.

Today it’s the city’s unofficial high-speed racetrack, bordered by some of the most fanciful turn-of-the-twentieth-century architecture on the Cote d’Azur.

The beach below the promenade des Anglais is all pebbles and mostly public, with showers provided. It’s not particularly clean and you need to watch out for broken glass.

There are, of course, the mattress, food and drinks concessionaries, but nothing like to the extent of Cannes.

There’s a small, more secluded beach on the west side of Le Chateau, below the sea wall of the port.

But the best, and cleanest, place to swim, if you don’t mind rocks, is the string of coves beyond the port that starts with the plage de la Reserve opposite parc Vigier (bus #32 or #3).

From the water you can look up at the nineteenth-century fantasy palaces built onto the steep slopes of the Cap du Nice.

Further up, past Coco Beach (bus #3 only, stop “Villa La Cote”), rather smelly steps lead down to a coastal path which continues around the headland. Towards dusk this becomes a gay pick-up place.

Roscoff

The opening of the deep-water port at Roscoff in 1973 was part of a general attempt to revitalize the Breton economy. The ferry services to Plymouth and to Cork are intended not just to bring tourists, but also to revive the traditional trading links between the Celtic nations of Brittany, Ireland and southwest England. In fact, Roscoff has long been a significant port. It was here that Mary Queen of Scots landed in 1548 on her way to Paris to be engaged to Francois, the son and heir of Henri II of France. And it was here that Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Young Pretender, landed in 1746 after his defeat at Culloden.

Roscoff itself has, however, remains a small resort, where almost all activity is confined to rue Gambetta and to the old port – the rest of the roads are residential back streets full of retirement homes and institutions. One factor in preserving its old character is that both the ferry port and the gare SNCF are some way from the centre.

The town’s sixteenth-century church, Notre-Dame-de-Croas-Batz, at the far end of rue Gambetta, is embellished with an ornate Renaissance belfry, complete with sculpted ships and protruding stone cannon.

From the side, rows of bells can be seen hanging in galleries, one above the other like a wedding cake created by Walt Disney.

Some way beyond is the grand Thalassotherapy Institute of Rock Roum, and a kilometre further on is Roscoff’s best beach, at Laber, surrounded by expensive hotels and apartments.

Royan Beach

Before World War II, Royan, at the mouth of the Gironde, was a fashionable resort for the bourgeoisie.

It is still popular – though no longer exclusive – and the modern town has lost its elegance to the dreary rationalism of 1950s town planning: broad boulevards, car parks, shopping centres, planned greenery.

Ironically, the occasion for this planners’ romp was provided by Allied bombing, an attempt to dislodge a large contingent of German troops who had withdrawn into the area after the D-Day landings.

But the beaches – the most elegant and fashionable of which is in the suburb of Pontaillac to the northwest – are beautiful: fine pale sand, meticulously harrowed and raked near town, and wild, pine-backed and pounded by the Atlantic to the north.

Ste-Maxime

Facing St-Tropez across its gulf, Ste-Maxime is the perfect Cote stereotype: palmed corniche and enormous pleasure-boat harbour, beaches crowded with confident bronzed windsurfers and waterskiers, and an outnumbering of estate agents to any other businesses by something like ten to one. It sprawls a little too much – like many of its neighbours – but the magnetic appeal of the water’s edge is hard to deny.

To enjoy the resort, however, requires money. If your budget denies you the pleasures of promenade cocktail sipping and seafood-platter picking (not to mention waterskiing, wet-biking and windsurfing), you might as well choose somewhere rather prettier to swim, lie on the beach and walk along the shore.

For the spenders, Cherry Beach (or its five neighbours on the east-facing plage de la Nartelle, 2km west from the centre towards Les Issambres), is the strip of sand to head for. As well as paying for shaded cushioned comfort, you can enter the water on a variety of different vehicles, eat grilled fish, have drinks brought to your mattress and listen to a piano player as dusk falls.

A further 4km on, plage des Elephants has much the same facilities but is slightly cheaper.

St-Raphael

A large resort and now one of the richest towns on the Cote, St-Raphael became fashionable at the turn of the twentieth century.

Its seafront Belle Epoque mansions and hotels, flattened by bombardments in World War II, have mostly been rebuilt, while the old town beyond place Carnot on the other side of the railway line has suffered years of neglect.

On rue des Templiers a crumbling fortified Romanesque church, the Eglise St-Pierre, has fragments of the Roman aqueduct that brought water from Frejus in its courtyard along with a local history and underwater archeology museum.

The beaches stretch between the old port in the centre and the newer Port Santa Lucia, with opportunities for every kind of watersport. You can also take boat trips to St-Tropez, the Iles d’Hyиres and the much closer calanques of the Esterel coast from the gare maritime on the south side of the Vieux Port.

When you’re tired of sea and sand you can lose whatever money you have left on slot machines or blackjack at the Grand Casino on Square de Gand overlooking the Vieux Port (daily 11am-4am), or there’s bowling at the Bowling Raphaelois on promenade Rene-Coty, and plenty of snooty discotheques.

St-Tropez

The origins of St-Tropez are unremarkable: a little fishing village that grew up around a port founded by the Greeks of Marseille, which was destroyed by the Saracens in 739 and finally fortified in the late Middle Ages.

Its sole distinction from the myriad other fishing villages along this coast was its inaccessibility. Stuck out on the southern shores of the Golfe de St-Tropez, away from the main coastal routes on a wide peninsula that never warranted real roads, St-Tropez could only easily be reached by boat.

The beach within easiest walking distance is Les Graniers, below the citadel just beyond the port des Pecheurs along rue Cavaillon.

From there, a path follows the coast around the baie des Canoubiers, with its small beach, to Cap St-Pierre, Cap St-Tropez, the very crowded Les Salins beach and right round to Tahiti-Plage, about 11km away.

Tahiti-Plage is the start of the almost straight, five-kilometre north-south Pampelonne beach, famous bronzing belt of St-Tropez and world initiator of the topless bathing cult.

The water is shallow for 50m or so, and the beach is exposed to the wind, and sometimes scourged by dried sea vegetation, not to mention more distasteful garbage.

But spotless glitter comes from the unending line of beach bars and restaurants, all with patios and sofas, serving cocktails and gluttonous ice creams (as well as full-blown meals).

Though you’ll stumble across people in the nude on all stretches of the beach, only some of the bars welcome people carrying wallets and nothing else.

Transport from St-Tropez to the beaches is provided by a frequent minibus service from place des Lices to Salins and Pampelonne, or a bus from the gare routiere to Tahiti, Pampelonne and L’Escalet.

If you’re driving, you’ll be forced to pay high parking charges at all the beaches, or to leave your car or motorbike some distance from the sea and easy prey to thieves.

Tregastel and Trebeurden

Of the smaller villages, Tregastel , with a couple of campsites, including the Tourony by the beach , and Trebeurden , with the seafront Le Toeno hostel, are functional stopovers.

Tregastel has managed to squeeze in an aquarium under a massive pile of boulders, and has a couple of huge lumps of pink granite slap in the middle of its fine beach.

Utah Beach

The westernmost of the main Invasion Beaches, Utah Beach stretches for approximately thirty kilometres south from St-Vaast.

From 6.30am onwards on D-Day 23,000 men and 1700 vehicles landed here.

A minor coast road, the D241, traces the edge of the dunes and enables visitors to follow the course of the fighting, though in truth there’s precious little to see these days.

Ships that were deliberately sunk to create artificial breakwaters are still visible at low tide, while markers along the seafront commemorate individual fallen heroes.