Things to do in Fort Sumner NM

Road tripping south on the 84 from Santa Rosa, New Mexico, you know you’ve to reach Fort Sumner when you pass under a historic railroad bridge – very tiny at that – dating from 1905. Then, this sleepy village unfolds along the banks of the Pecos River. The 84 makes a turn here, forming a T, and the main street.

There are a handful of restaurants and Mom ‘n Pop shops, with a few gas stations, tossed in. Several murals cover the walls of buildings, and most of the structures have seen a more prosperous time. Still, it retains some of yesteryear’s charm.

Fort Sumner’s current claim to fame is being the center for the irrigation district – farmlands spread out across the plains in each direction. The main crops are alfalfa, sweet potatoes, apples, and melons, with a handful of grapevines struggling to cling to wires. There is also some cattle and sheep ranching.

Life has a slow feel, and when you order a cup of coffee from Darland, the staff actually wants to talk to you. The first thing noted is, “You’re not from around here.” I sipped my coffee, watching others come and go. Even though a festival was going on down the street, the pace was still molasses-like.

History of Fort Sumner

This wasn’t always the case.

Fort Sumner began as a trading post. For over a hundred years, it served the Spanish, Mexican, Apache, and Comanche communities. Then, American settlers began encroaching on the land. A full-on war broke out in 1849, when a Navajo leader, Narbona, was murdered by U.S. soldiers. In response, during the 1850s, several forts were built throughout the area. By 1858, the Navajos were forced to sign the Treaty of Bonneville and they were stripped of much of their ancestral land.

The bloodshed only temporarily halted, and raids and counter-raids were frequent between Fort Defiance and the Navajo warriors. A second treaty was signed and was violated just as quickly.

Then a horse race was held between the warriors and U.S. soldiers, as a form of entertainment. One of the soldiers cheated but was pronounced the winner anyway. The Navajo formed a mob, upon which the soldiers opened fire, killing thirty people.

The plan to remove the Navajo from the native land was put into motion. This was to be the ultimate punishment, as leaving Dinetah (the native land) and crossing three rivers would bring bad things to the Navajo. Eventually, they were forced to cross the Rio Puerco, Rio Grande and the Pecos River. The warning was about to become a reality.

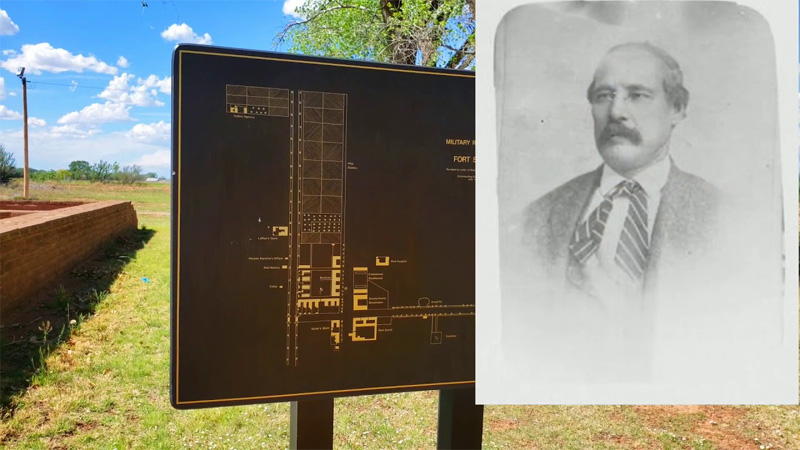

Fort Sumner, named for a military governor, was built in 1862. It was designed to stop the raids on the settlers in the Pecos Valley. The first reservation west of the Oklahoma territory was established nearby and it was named for a grove of cottonwoods in the area, Bosque Redondo.

Here, the Navajo and Mescalero Apache learned to farm, had Christianity forced upon them, and their children were ordered to attend school. They were to be ‘civilized.’ Between 1864-1866, over fifty-three different marches relocated the tribes to the reservation: the worst of these became known as the ‘Long Walk.’

Kit Carson, due to his success at subduing Apache tribes, was appointed to the task. He had orders to seize all the Navajo and to kill those who resisted. He hunted and captured a large group of people in the Canyon de Chelly area in Arizona. Carson burnt their homes, supplies, and two million pounds of corn, along with their sacred peach trees. He slaughtered their herds then starved them into surrendering.

Over the course of eighteen days, the Navajo walked 450 miles. Some drowned when crossing the Rio Grande. Others fell to diseases such as pneumonia, dysentery and smallpox. Stragglers, including pregnant women, children, and the elderly were shot and left unburied next to the road.

When they finally arrived at Bosque Redondo, life was no better. The Navajo and Mescalero Apache have sworn enemies, and now they had to live together. The reservation was designed to hold five thousand people. Over nine thousand were relocated. There wasn’t enough water or firewood and the 1867 crops failed.

Navajo leader, Barboncito:

Whatever we do here causes death. Some work at the acequias [irrigation canals], take sick and die; others die with the hoe in their hands; they go to the river to their waists and suddenly disappear; others have been struck and torn to pieces by lightning. A rattlesnake bite here kills us; in our country a rattlesnake before he bites gives us warning which enables us to keep out of its way and if bitten, we readily find a cure – here we can find no cure.

One-third of those who arrived perished during internment. The Mescalero Apache escaped, but the Navajo stayed until 1868 when the U.S. government realized that the reservation was a failure. A treaty was signed, granting the Navajo 3.5 million acres of their homeland, to the northwest. (The reservation, primarily based in Arizona, has since grown into the largest in the United States, at sixteen million acres). On June 18, 1868, a ten-mile long column of tribal members left Bosque Redondo for good.

Two years later, the forgotten fort was sold to Lucien Maxwell, the largest private landowner in the world. He had already purchased 1.7 million acres in New Mexico and Colorado when he bought the Fort Sumner property for $5,000. (At this point, the government was financially drained due to the Civil War.) Maxwell renovated the fort, turning it into his home, where he lived until his death.

Lucien’s son, Peter, had befriended William Bonney (a.k.a. Billy the Kid), who was actually shot to death inside the Maxwell home. In 1884, the Maxwells sold the property.

In 1905, when the railroad came to the area, Fort Sumner moved seven miles northwest, next to Sunnyside. The two towns merged in 1909, after purchasing the land of the failed reservation.

The next biggest event in the town’s history came nearly seventy years later: NASA. Every spring and autumn, high altitude balloons are still launched just northeast of the town.

During the 1920s, an airfield was built by the Transcontinental Air Transport company, in order to establish a passenger service. It closed during the Great Depression. Then, in WWII it found a new life as a training base, and afterward as a municipal airport.

Bosque Redondo

In 2005, a monument to those lost at the Bosque Redondo was designed by Navajo architect David Sloan. It is shaped like a teepee and hogan (sacred Navajo dwelling) and can be found southeast of Fort Sumner, on Billy the Kid Road.

The area is, once again, ringed by cottonwood trees, and the path leading to the entrance takes the sacred way of the Navajo into its design. Once inside, it’s very sparse and apparently still in phase two of development. There are a few signs, some pottery, and a thirty-minute video – which didn’t work when I visited. Maybe wait a few months and call to see if any progress has been made?

Old Cemetery

Just down the road from the monument is the Old Cemetery, which holds the bones of Billy the Kid. Billy allegedly killed a person for every year of his life, making a total of twenty-one. Except that the actual number of victims was closer to nine. Most of those shootings occurred during the Lincoln County War – essentially a turf battle between rival gangs, which escalated into a five-day killing spree.

The new sheriff of the territory, Pat Garrett, was given the task of cleaning up the county and first on the list was Billy. Garrett captured the Kid, who was convicted and sentenced to hang. However, he escaped, killing two guards along the way. The Kid hid out in Lucien Maxwell’s house. Garrett arrived to question Maxwell about the whereabouts of the Kid and the two stumbled into each other. That was the end of Billy. Or, so one version of history goes. Another states that the Kid escaped again and fled to Texas, where he led a low key life.

The cemetery is sparse in terms of tombstones. This is due to flooding: the cemetery was submerged under four foot of water and the wooden crosses floated away. So, it’s anyone’s guess where Billy’s body is actually buried. I suspect they picked a random spot and King Vidor, the director of a film based on Billy’s life, coughed up the cash for a granite tombstone.

That’s not quite the end of the story. The original stone was stolen in 1950 but was recovered in 1976 in Granbury, Texas. A few years later it was stolen a second time but recovered much quicker. Now the tombstone and one marking the graves of Billy’s friends are both locked up in a steel cage.

It is free to see Billy’s tombstone, but admission to the adjacent museum costs $4. It contains a lovely collection of junkyard finds, which may or may not have anything to do with Billy himself.